How Values Get Lost in Translation

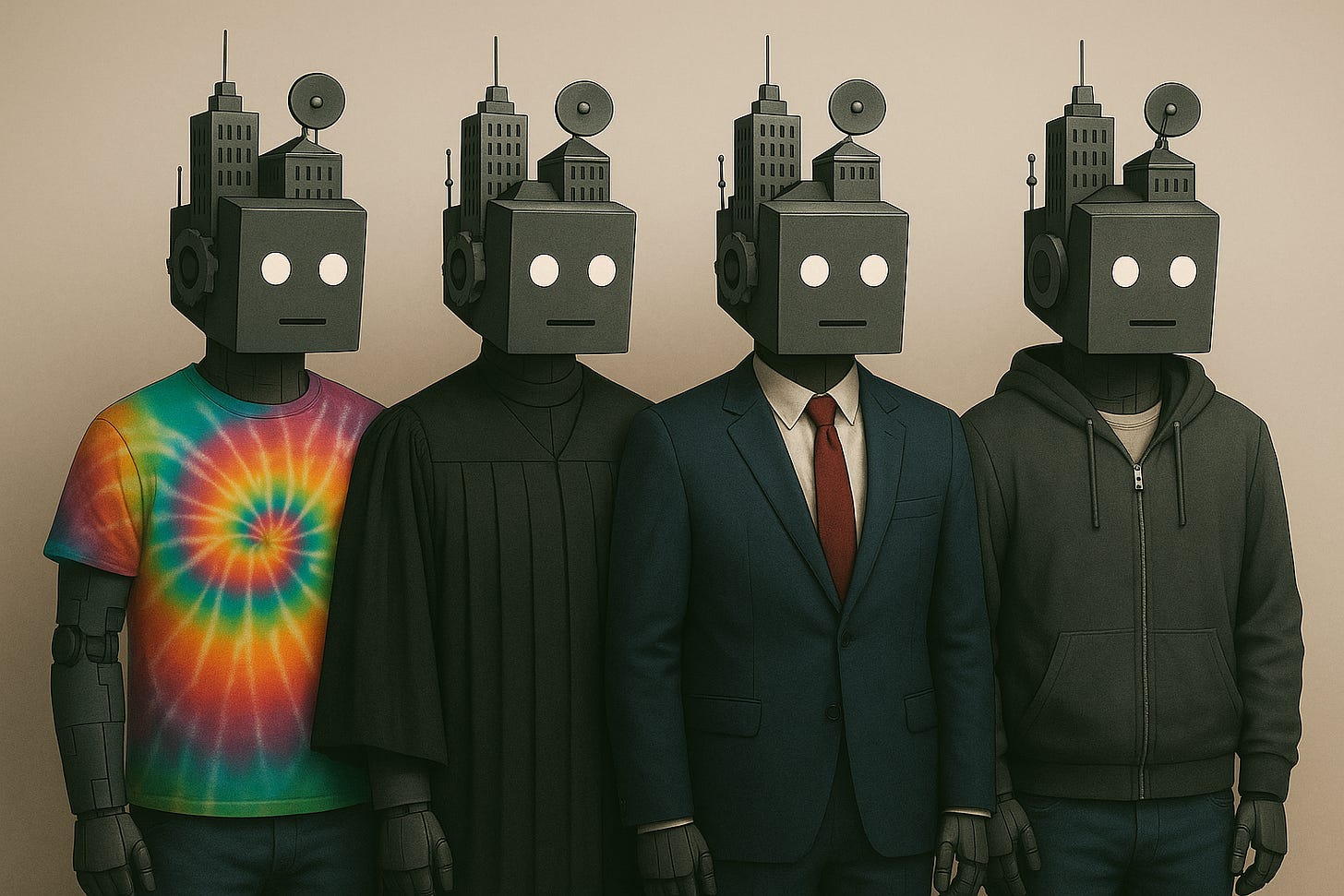

A framework for how human values move (and get lost) through law, organisations, and interfaces.

I was having an imaginary conversation with an institution a while back. We were in the middle of a fairly significant disagreement and I was finding that the human agents it was sending to represent itself could only speak within their very limited areas of responsibility. If I needed one of them step back and look at the big picture they couldn’t. Not because they weren’t willing, but because they weren’t allowed. That’s a product of intentional design, but we’ll come back to that some other time. What’s important here is that to get my thoughts together, I imagined talking to the institution itself about the problems I was having with it.

It went something like this:

“I’m really not happy with this,” I said.

“What aren’t you happy about?” the institution replied. “Do you not understand the process?”

“I mean, I only kind of understand it. It’s your process and I’m only really seeing how it interacts with me. I don’t see what happens with it once it goes inside the organisation.”

“Of course, that’s operationally sensitive.”

“So you say. But that’s one of the things I have an issue with. It’s your process, if I want to interact with you, I have to comply with it.”

“Yes, that’s how it works.”

“But your process is harmful, I can see that, and I think that the people you’re having me talk to know that too. I’ve tried to suggest another way of doing things, maybe using my preferred way to solve this, but they can’t seem to do that.”

“No, everyone needs to follow the process.”

“Yeah, so you keep saying. But here is the thing: I have an objective that I need to achieve, because you stuffed up. I mean, it’s been proven that it was your fault, we’ve established that. I don’t have a choice but to follow your processes if I want to get this resolved. You won’t follow mine?”

“Yes, that’s correct.”

“And that’s ok by you?”

“Yes, if you want this resolved you need to follow the procedure.”

“OK here is my problem with that – if this were happening between two people that would absolutely be a case of you denying me agency.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Of course you don’t. I mean, at no point have you regarded me as a whole person. Instead, you turn me into a series of signals. Documents. Forms. Bits of testimony. Nothing that adds up to a person. All I’m suggesting is that you nominate someone who I can talk to. They can take a look at all of this (gestures vaguely) and make a sensible decision, save us all a lot of time and frankly a lot of money for you, and stress for me.”

“Why would I do that? I’m following the law, I don’t have to consider human agency. Doesn’t matter to me what happens here or how long it takes, so long as I comply with statutory requirements.”

“Well as an entity with moral agency talking to one without it, I’m telling you that you need to start considering human values.”

I then heroically punched the institution and walked away having expertly made my point.

We all struggle dealing with institutions

There’s a reason why these conversations are the product of imagination. I’m trying to reason with an incoherent intelligence that understands goals and liability but can’t possibly relate to me on my terms. It’s bigger than me, more powerful, and a lot wealthier, but isn’t my equal.

Even if I could sit down with the CEO of this institution, they’d probably refer me to specialists within subunits to deal with my issues. And most likely they’d all be pretty accommodating, to the extent that they can be. Their ability to act on their values is sharply constrained the moment they put on the lanyard. I know this, I’ve been on the inside of these systems for my whole career.

Most of you will have a version of this story. It might be a company that doesn’t listen, a form that didn’t fit, a process that delivered a pyrrhic victory after amplifying harms along the way. Sometimes that is translated into frustration with the individuals involved. Occasionally that frustration is justified, especially when an individual has made a harmful, accountable decision. But it’s more likely that the inconveniences, frustrations, injustices, and harms caused by institutions is the product of behaviours which emerge from the structural features of systems rather than the behaviour of any individual.

It’s a liberating perspective. It means that when you encounter a stranger you can still begin your interaction with the assumption that they are much more likely to be good than evil, regardless of what they were doing between nine and five.

You also realise that there is no way that these systems, as they are currently structured, can account for our values in the way that we do. They don’t have a moral sense. They’re not bad, they’re just drawn that way.

Organisations clearly have values. The individuals in best ones that I’ve worked for live by them, top to bottom. Broader systems are established with values in mind. They are the scaffolding supporting the logic of their design. Governments are the same. Their founders brought them into existence following intense deliberation of how people and power should relate to one another.

At their core though, organisations are goal-driven. Values, when they exist, are often narrower than those of a person, and nearly always subordinate to operational objectives. Most of the time that goal is returning a profit. But even this is based on a value: that those who own something should receive more benefit from it than those who don’t. It’s rarely articulated and is certainly not something that I consider when catching the train to work in the morning. But it’s there humming in the background of our collective cultural subconscious all the same.

And so, I started thinking more seriously about how values interact with systems and how they get encoded, distorted, or overridden entirely. When I talk about systems here, I mean systems that are designed by humans, as opposed to natural processes or individual minds. This includes companies, charities, economic architectures, treaties, and infrastructure systems like power grids. These are structures we’ve built, sometimes deliberately, sometimes carelessly, but always with values embedded, whether we intended them or not.

We built these systems to help us achieve our goals. All of it was made by humans. And when you step outside the daily noise and take it all in at once you realise that it’s an extraordinary achievement.

We gave them eyes and ears, hands and minds, the tools to remake the world. But we didn’t give them our greatest feature: hearts to feel with.

That wasn’t an accident. It was a design decision.

Fittings values and systems into a framework

It’s possible that I’m not being fair to our forebears. The original ideas of these systems included an assumption that the individuals leading them would have a sufficiently detailed understanding of their organisations and sufficient authority that they could correct any moral failings within their power. This was a product of organisations being far less complex and of their leadership being drawn out of social classes where reputation was a critical consideration.

We don’t have that today. Organisations are enormously complex and essentially run themselves through established processes, culture, and compliance with the law. I have this feeling that while the increase in the number of laws has ensured that systems stay within the minimum requirements of moral expectations, it has also limited the ability of well-meaning executives and staff to exercise moral discretion. Still, laws constraining systems are essential, valuable, and, on balance, a massive social good for the community. It is the tool we have for managing these challenges.

It was in thinking about this interaction between values, laws, organisations, and humans, that I started to build up a framework to help me to understand how shared values interact with the systems in our lives. It has helped me to uncover gaps, the places where systems misfire or drift, not because they’re broken, but we never structurally embedded the values we claim to hold.

The model that follows fits it the category of useful rather than as a reflection of objective truth. The borders between the layers are fuzzy, they sometimes contradict each other, and some outliers refuse to be coerced into the model. But it remains useful as a map of how values move from culture to code.

The framework has four layers:

Values layer

Meta-systemic layer

Implementation layer

Interface layer

The values layer

The values layer is fairly straightforward, at least on the surface. We understand values instinctively. Values are human tools which we’re naturally attuned to. They enable cooperation, trust, and social cohesion. We’re not rational actors in a vacuum; we’re moral animals embedded in context. We have language and narrative that allows us to encode and transmit values between individuals and generations. We feel emotions like shame when we violate our values, a reflective safeguard against acting in ways that might lead to exclusion from a group. It’s an embodied instinct against violating invisible contracts, more about social survival than logic. And we have a theory of mind that allows us to judge not just actions but intentions. This means that we can infer violations of values from observations of actions based on the objective that an agent is trying to achieve.

Of course, once you delve further into it, the values layer becomes much more complex. To fit into a framework, you need to have definitions, categories, and structures. As fuzzy human vibes, values resist fixed boundaries and standard definitions. We each have an idea of what freedom, democracy, agency, and loyalty mean, and while there is significant overlap among the population, there is enough variation to fuel centuries of ideological conflict. Ten lines chiselled into stone tablets three thousand years ago has spawned entire libraries of interpretation. And even then, we still argue about what “do not kill” means in context.

I tend to think of values as relational attractors, central nodes in the web of ideas we hold. A concept like consent gains meaning not in isolation, but through its proximity to liberty, responsibility, harm, and power. These relationships serve to put the value labels in a position in our worldview and allow us to understand what we mean by its context. They then act as constraints on our behaviour, informing the decisions we make and actions that we perform. These constraints are instinctive or emotional, we don’t logically think through every situation to decide how it fits with our values.

Even though our values differ in the details, there’s a shared architecture beneath. We may disagree on the bounds of freedom, but we know what kind of thing it is, and what kinds of debates it belongs to. There has to be, otherwise there could be no shared understanding. They are a thing, and like other things, they can be subject to categorisation and shared understanding. This understanding is contextual, particularly to a culture or language, but it means that a society can generally agree on what a specific value means, even to individuals who don’t hold those values. I would however assert that there are a core set of values that adherents to a worldview share which are the most fundamental inputs into the logic we use to build our societies.

The meta-systemic layer

Following the values layer is the meta-systemic layer. This layer is the system of systems, or the underlying encoded principles that a society uses to describe how it operates. In this layer you have things like constitutions, laws, financial systems, and conventions. They tell a society what is permitted, how government is to be constituted, how courts operate, what activities individuals and institutions should perform. If the values layer is the design principles of a society, then the meta-systemic layer is the operating system.

This is where abstract ideals are formalised into enforceable logic. It draws from the values layer and pushes downward into the implementation layer and the systems that govern our lives. Values are encoded here as the principles which become regulations and laws. Some of these values are explicitly expressed in documents, while others need to be decoded from the text within a cultural context. This layer ranges from critical societal documents like constitutions all the way down to more procedural laws passed by parliaments.

Constitutions in democratic states are a prime example of a meta-systemic layer artefact. Within them they describe things like methods of electing representatives, how laws are to be passed, the powers of government, and the separation of powers. The logic behind these architectural decisions flows directly from the values of the culture, whether assumed or explicitly stated.

The Constitution of the United States is an excellent document to examine using this framework. If we take the example of who is eligible to run for President, we see the document states that the individual must be over the age of 35 and must be a natural-born citizen. The document doesn’t state why these criteria were chosen, but we can infer the values they reflect by interpreting them in cultural context.

The age limit requirement encodes an implicit belief that leadership at the highest level requires life experience and a level of psychological maturity that it’s presumed are less likely to be found in a younger person. It reflects the societal value that wisdom grows with age and experience. It’s something that the citizens of Naboo should have considered in the design of their government.

The natural-born citizen requirement encodes a different value: that national leadership should be entrusted only to those with an unbroken bond to the nation itself. It privileges loyalty born of birthright. In the context of a young republic that had just fought a war to establish independence, this makes cultural and historical sense.

In this way, the meta-systemic layer serves as a translational layer between the human domain of values and the procedural logic of systems. It takes the fuzzy, context-rich language of culture and formalises them into durable structures that can be interpreted, enforced, and acted upon. In doing so, it renders values legible to institutions. But this translation is never perfect. Some values are preserved explicitly, while others are only visible when decoded through history and cultural context. And some are lost entirely in the shift from moral intuition to systemic rule.

The implementation layer

The next layer, the implementation layer, is what we will normally think of when talking about human systems. For the most part, these are the institutions that run the world. We have governments, companies, departments, militaries, charities, political parties, communes, all sorts of organisations. They have different goals and different operating structures, but they all act to implement the principles defined in the meta-systemic layer. In this layer the structures laid out above become policies, workflows, protocols, and behaviours.

There are also certain professions who operate at this level. I call them role-based actors. It generally includes people who operate under a license and have individual responsibility within a system. The best examples are doctors, lawyers, accountants, and judges. Their roles are system-sanctioned, and they have a high level of autonomy and accountability within the scope of their profession. There are also officers with delegated authority in this layer as well, but this gets complicated quickly, so we’ll leave it for now. But it’s important to note that there are individual professionals who fulfil roles similar to institutions in how they function in our systems.

Where this gets interesting is that these role-based actors have codes of ethics that they must abide by. Institutions do not. There are some good reasons for this, most practically that we don’t build institutions with a moral sense. But the threshold for operating for institutions is that they only have to comply with the law. This is clearly a misalignment, one that we instinctively recognise when we insist that role-based actors behave according to strictly defined values.

The systems at the implementation layer are vastly overrepresented in our society. It’s where most of the effort is focussed because it’s where the goals are achieved. But they’re also hyper-formalised, rigid, self-preserving, and deeply legalistic. It’s where governance is assumed to reside, but it only really executes rules and structures handed down from elsewhere.

I’ll be spending a lot of time on this subject over coming posts. But for today I’ll just say that I believe that in the imperfect translation from values to meta-systems to systems we lose an enormous amount of the nuance of human values. They’re kind of there, but they get lost unless they are explicitly safeguarded under a regulation. It’s my suspicion that the misalignment of these systems, which dominate our world, is a core cause of the quiet discontent we all feel.

The interface layer

Finally, we have the interface layer. This is any time that a system is interacting with a human or other systems. It’s at this layer that we get user interfaces, forms, system-to-system standards, call centres, and customer service centres. Systems operating at this layer have strict protocols about how they communicate and interact with humans, a translation of human requirements into the system’s inner logic.

Often at this layer a human is reduced to signals that the system can interpret. It might be a diagnostic decision for an insurance claim, a fault code for a warranty repair, or a checkbox on a form that determines eligibility. The person disappears behind the inputs, and interaction becomes conditional on what the system is designed to see and respond to. This is also where the constraints on a system become most visible to human individuals.

Our frustration with the systems we interact with is often complex and individual. But systems respond to this with rigid processes and a flattening of a unique human into a comprehendible dataset. This can create frustration and exclusion, or even harm. A value like agency, dignity, or consent can be lost at the interface, simply because it was never encoded as something the system could recognise or respond to.

The concern that runs from top to bottom in this framework is that the values are lost in translation as they propagate down the four layers. Our values clearly exist, we have a rough idea of what they mean, and in general we expect our systems to behave in a way that is consistent with them. But we haven’t built in the internal logic, signals, feedback loops, and incentives to make systems sensitive to violations of our shared values. We struggle to even articulate what our values are. This is a critical oversight of our civilisation which has contributed to some catastrophic failures. It’s worsening as increasingly complex systems take over more of our lives.

The good news is that AI presents an opportunity for us to fix this. As artificial intelligences become the systems, it will compress bureaucracy and allow values to be considered through the logic of entire institutions. This means we can reimagine how human agency interacts with institutional structure.

That’s where I’m going next. Stay tuned.